Though men from Central Kenya love sons, it is the daughter named after their mother who becomes the apple of their eye

By Mbatia wa Njambi

Visiting Thinker

The Kikuyu man has a thing with his mother: She is mostly the one they name as next of kin in bank and other documents where property and money are involved- not the wife.

When he wants to confirm the wife did not play away games, it is to the mother he runs to for matriarchal reassurance that his kid’s ears resemble those of grandpa Kimondo and therefore there is no reason for raising the blood sugar.

Though Kikuyu men are proud and yearn to sire sons, it is the daughter named after their mother who becomes the apple of their eye. Indeed, during separation and divorce cases, the callow youth in the Kikuyu boy invariably sides with the mother-sometimes no matter how rich the father is.

The most curious thing about Kikuyu men is their adoption of their mother’s surnames for social and official identity

But the most curious thing about Kikuyu men and their mothers is the adoption of their mother’s surnames for social and official identity.

It is a trait peculiar to Kikuyu men more than any other community in Kenya. Okay, Luo men sometimes use them, but only when Aristotle Kanyadudi earns his PhD in ‘Anatomy of a millipede and its application to groundnut farming in Ahero.’

Onwards the freshly minted PhD graduate drops Aristotle for Kanyadudi McAtieno. McAtieno means ‘son of Atieno.’ The new maternal linkage, however, is a sign of cultural defiance and badge of upgraded academic status as Dr Kanyadudi McAtieno, than for long-binding traditions.

The surname is an insignia that gains new dimension if she was a single mother

For the Kikuyu, it is different: The mother’s surname is an insignia of her centrality in his life even if the father was around. But it gains new dimension if she was a single mother.

But this pride was not always the case in post-independent Kenya. Men married many wives and being a single mother was the exception, not the norm. However, perceptions changed with women empowerment through education, creating a constituency of single mothers especially in Central Kenya. Using a mother’s surname, thus, did not come with as much stigma as in the 1970s and 1980s.

Opinion leaders like musicians, priests and politicians took pride in their mother’s surnames too

Widespread acceptance was gradually cemented after opinion leaders like musicians, priests and politicians took pride in their mother’s surnames.

Musicians influence huge populations via the power of song craft. The most pervasive musicians in Central Kenya was the late Joseph Kamaru who preferred adding the moniker ‘Wa Wanjiru” meaning son of Wanjiru. So did Musaimo wa Njeri, DK Kamau wa Maria, Jimmy Wayuni (for Eunice) Peter Kigia wa Esther who even named his music production outfit, Wa Esther Productions.

These musicians also composed praise songs honouring their mothers, rarely their fathers. Those who did use their mother’s surnames adopted their daughter’s named after their mothers. The late John De’Mathew was called ‘Baba Ciru’ which was also the named used by the late rally driver Ben Muchemi ‘Baba Ciru.’

Even elite athletes like marathoners Samuel Kamau became more famous as Samuel Wanjiru

Then there were Kikuyu politicians like former Nairobi Town Clerk Kuria wa Gathoni and current Githunguri MP Kago wa Lydia. Catholic Priest Fr Ndikaru wa Teresia even used the name on the cover of A Voice Unstilled, the 2009 memoirs of Archbishop Ndingi mwana a’Nzeki co-authored with Waithaka Waihenya.

Even elite athletes like marathoners Daniel Wanjiru and the late marathoner Samuel Kamau became more famous as Samuel Wanjiru, the name used when he won gold medal during the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Who can forget the rogue doctor named Mugo wa Wairimu?

Kikuyu men also prefer associating with parent they’re sure of since the father could not be the biological one

Why is the use of mother’s surnames peculiar to Kikuyu men and most pervasive custom in Central Kenya? Well, few of the 42 Kenyan communities are as matriarchal as the Kikuyu.

Fr Peter Kiarie, a Catholic Priest argues that Kikuyu domestic structures mostly polygamy played a role in sons identifying themselves with their mothers to differentiate themselves from other children of other step-mothers. “Even in this age of monogamy, naming yourself after your mother continued as part of tradition,” he says adding that “Kikuyu men also prefer associating with parent they’re sure of since the father could not be the biological one.”

While some Kenyan communities name children after seasons, the Kikuyu name theirs after blood relations

Fr Kiarie also singles out the Kikuyu naming system which is also peculiar to the Kikuyu than any other community in Kenya. “While some Kenyan communities name children after seasons, the Kikuyu name theirs after blood relations with the first daughter being named after the man’s mother. This creates affinity to a mother’s name.

Then there is economic empowerment of women in Central Kenya.

Eminent economist and certified bride price negotiator Dr X.N. Iraki wrote in one of his Sunday Standard articles that “from my observation and conventional wisdom, empowered women are finding it hard to get “quality” men to marry them. And you can guess right, more children are being born out of wedlock. It was rare when we were growing up. Fines and ostracization made many girls marry and raise children. We seem ill-prepared for the unintended consequences of women empowerment.”

If a man can’t name a kid, what other power does he have?

Dr Iraki notes that economic and political empowerment took root in Central Kenya more than anywhere else in Kenya and for several reasons. Early contact with the White colonialists and missionaries opened doors to western values among them capitalism and educational pursuits. The two end up molding a woman who is independent even when married.

Dr Iraki writes that “the power of women in this region is best espoused by their children’s surname like Kamau Njeri or Kinuthia Wairimu. This is culturally unprecedented. If a man can’t name a kid, what other power does he have?”

Mother’s surname has roots in the mythical origins of the Kikuyu

But entrenchment of using a mother’s surname has roots in the mythical origins of the Kikuyu community and the impact of colonialism in Central Kenya.

For starters, women take a central role, not only in the community’s mythical origins from ten daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi, but also in descent, identity and governance as Kenyan anthropologist Louis Leakey notes in his book, Southern Kikuyu before 1903 and in which he traces matrilineal societies as being mostly farmers while patrilineal ones were pastoralists like the Maasai.

Is the propensity of mother’s surnames out of affinity for Kikuyu clans which are feminine?

Leakey notes that it was the nine daughters of the Agikuyu who took husbands not the other way round lighting up the matriarchal fire such that to date, the community collectively calls itself the House of Mumbi-where single mothers were not forgotten.

The Kikuyu, it is widely believed, come from the nine clans, but there was the 10th clan named after their 10th daughter, Warigia (meaning the last one) also called Wamuyu who did not find a husband, but gave birth with one of the nine from the sisters.

The 10th daughter, a single mother, became the poster girl for all unmarried Kikuyu women with children. To date, all Kikuyu men born of single mothers belong to the Wamuyu clan thus strengthening attachment to maternal lineages.

Political leadership was the other source of entrenching matriarchy. Before the coming of British colonialists, Kikuyus were governed by Age Groups (Riika) in generational rotations. But the entry of colonial rule in Kenya ended all that when the Mwangi and Maina Riika were about to transfer power between themselves.

Wangu wa Makeri was the only woman headman in Colonial Kenya

To date, every Kikuyu man is either a Mwangi or a Maina in the Riika power structure which comes into play during traditional ceremonies.

The end of leadership through the Riika, the colonialistsushered in the era of women leaders the most famous being Wangu wa Makeri, the only woman headman in Colonial Kenya. Paramount Chief Karuri wa Gakure, and after whom Karuri town in Kiambu County is named, appointed Wangu-his side dish- the headman for Weithaga Location in Murang’a County in 1901.

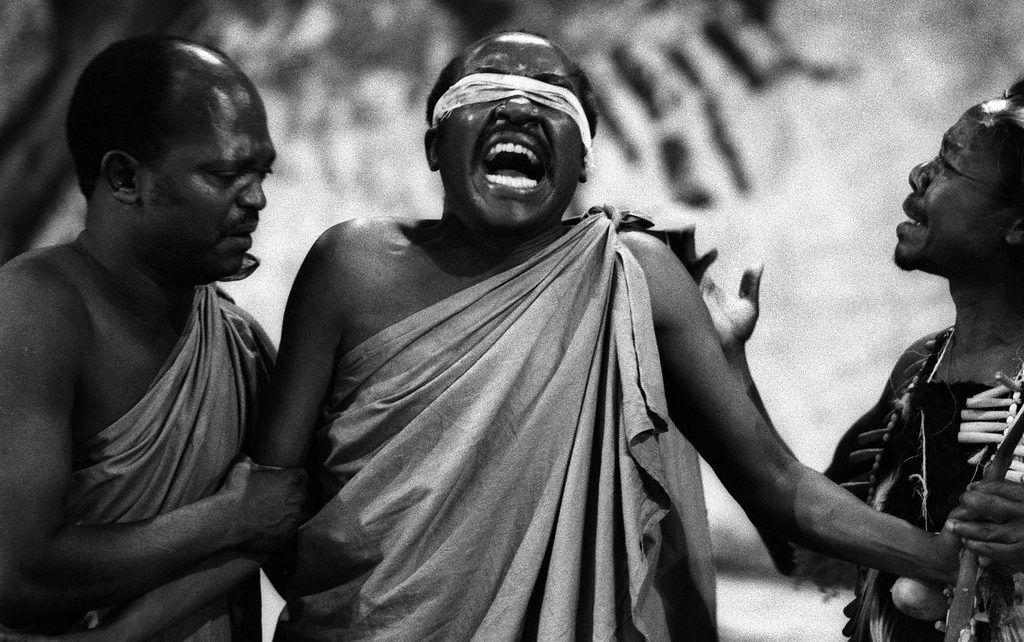

Wangu wa Makeri collected taxes for the colonial government from men in ways that would have made Adolf Hitler proud. She not only sat on men, but also humiliated them in public using her sidekicks-Jeshi La Mama-which locked up offenders.

Though the man is the head of the house, it’s the woman who controls decision making: where to live, which property to acquire, where to worship, what to eat

Although her brutal rule ended in 1909 when she gate crushed a male adult only dance and wriggled naked and the Iregi Age Group spearheaded a revolt , Wangu wa Makeri entrenched matriarchy in power structures such that, even today, the Kikuyu have no heartburn electing women as MPs, Governors, Woman Reps and MCAs, more than any other community in Kenya.

These matriarchal nature of the Kikuyu community trickles down from open leadership of elected office to the closed one of domestic turf at home where, though the man is the head of the house, it’s the woman who controls decision making: where to live, which property to acquire, where to worship, what to eat.

Kikuyu woman became the father, mother and source of security

Long lasting usage of a mother’s surname by Kikuyu men was glued inadvertently through colonial rule, and the State of Emergency which was declared by Governor of Kenya Sir Evelyn Baring in October 1952.

The State of Emergency lasted only seven years but the effects included creating a social crisis, domestically splitting up families.

American historian Caroline Elkins in Britain’s Gulag: The Brutal End of Empire in Kenya published in 2005 notes that Kikuyu were either in the forest fighting as the ‘active wing’ of the Mau Mau or in detention as part of the informers arrested after being implicated as members of the ‘passive wing’ of the Mau Mau.

This left Kikuyu women to fend for their children besides bearing the largest blunt of violence from the Colonial police, the Tribal Police and the Home Guards. The Kikuyu woman became the father, mother and source of security and food at a time when freedom of movement and associated were restricted.

Most were confined to Emergency Villages, over 800 of them with 240, 000 mud huts in Central Kenya after the British not realized Kikuyu women were the passive “eyes and ears” of the Mau Mau.

Around 10 women and their children shared a room where they also cooked and relieved themselves. There was no going out past 6pm for the over one million Kikuyu in the villages. Women in ‘emergency villages’ tilled their land, milked their cows, carried out daily household chores in Home Guard farms as their wives were exempt from work.

The image of their mothers holding domestic reins in the seven years the State of Emergency lasted has seen a whole generation of Kikuyu men take their mother’s surnames with masculine gusto in a tradition that is not about to end over 50 years after independence.

Note: The editor welcomes well argued essays on topical issues not more than 2000 words- editor@undercoverafrica.com

I agree partly, especially where he quotes X.N Iraki and the possible effects of the emergency on the collective psyche of the children of that time. I feel that it (surnames) is a culmination of the collective Kikuyu experience rather than an avant garde example or testament to our progressiveness. We adopt quickly and have decided that fathers are not important, lol. He is wrong when he says we are matriarchal… land and other assets ownership levels say the contrary. We are matrilineal. We trace our lineage to our mothers because of our naming system. Ultimately, this ‘special place of Kikuyu women ‘ is serendipitous as opposed to a deliberate process at women empowerment. You can find parallels with women in the West who took up ‘men’s jobs’ during the world wars and were liberated thereafter, earning the right to vote for instance. It is a classic case of giving an inch and ending up succumbing to pressure and giving up a mile. My take.