Majority of those who scale the financial uplands do it in the easiest ways known: Solving human problems and charging for it

By GW Ngari

Editor-at-large

Not one Kenyan made it to this year’s list of Africa’s dollar billionaires, basically those whose worth kisses the Sh100 billion ceiling. The Kenyattas and the Ndegwas play in that diamond league but are not among the top 20 in the Forbes Africa list.

The bulk of dollar billionaires in Africa coin their dough through manufacturing, banking and diversified investments, but Chris Kirubi of Haco Industries and Kimani Rugendo of Afia juice, steel and cement magnate Narendra Raval are missing out as is Manu Chandaria of Comcraft Group and Vimal and other Shahs at Bidco Oil Refineries.

Raval the ‘Guru’ of Devki Group was valued by Forbes at $400 million (Sh40 billion) while the Bidco fortune is owned by the assorted Shahs diluting their stakes to below Sh100 billion each. That leaves Manu Chandaria whose Comcraft Group was valued at $2.5 billion by Forbes nine years ago.

That means Manu, who has worn one watch for 65 years, is easily Kenya’s richest at Sh250 billion, but the Comcraft bread whose margarine is spread across manufacturing roofing sheets and aluminum products, is shared among the Chandaria blood relations. “It is not my company,” the man who has five suits and one wife clarified in 2018. “It’s a family owned business where everyone has responsibilities.”

Half of the high rollers made it through inheritance- the easiest route to making money-you gladly receive!

Scheming, planning, plotting, musing and dreaming how to become Mr Moneybags, takes time

Like Mohammed ‘Mo’ Dewji of Tanzania, the only East African on the list at $1.6 billion (Sh160 billion) of inherited wealth in textile manufacturing, flour milling, beverages and edible oils with markets in eastern, southern and central Africa.

Mo Dewji, one time MP is, however, 16th overall in Africa. The man who launched Mo-Cola to compete with Coca-Cola, made global news after being kidnapped at gunpoint in Dar-es-Salaam in 2018, but was later released nine days later.

He is also the youngest at 44, the oldest is 76, meaning no matter how many sleepless nights you roll in bed wondering, scheming, planning, plotting, musing and dreaming how to become Mr Moneybags, being a financial Kahuna, takes time.

Something else: Being employed (and now working remotely) won’t make you the billions. All of Africa’s richest (and only two are women from Angola and Nigeria) are business owners mostly in manufacturing, mining, telecoms, energy, chemicals, banking, insurance, construction and diversified investments in several countries.

Forbes Africa calculated their net worth from listed stock prices multiplied by current currency values as at February 2020. That means if the calculations were repeated now the names on the list would change considering the financial damage dealt to businesses by the ongoing pandemic. For privately held business, Forbes is guided by estimated annual revenues and profits.

Kenya’s overbearing tax regimen which forces many to hide their wealth

Forbes finds it hard cracking Kenya’s richest for several reasons. One is Kenya’s overbearing tax regimen which forces many to hide their wealth from the bean counters at the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) via investing through nominee accounts, shell companies and stashing money in tax havens.

Even former KRA Director General, John Njiraini, then the chief tax collector, saw it prudent to register his investment arm, Decamis Ltd in Hong Kong, a tax haven, according to court papers filed in 2018. Through Decamis Ltd, Njiraini held a minority stake at the Sh1.3 billion Space & Style Ltd, the dealers of decra roofing tiles, but whose shareholder battles exposed Njiraini in court.

This year, Attorney General Paul Kihara-President Uhuru Kenyatta’s cousin-issued a raft of regulations which among others; would force the disclosure of names, PIN, phone numbers and home addresses of investors owning more than 10 percent in listed firms under nominee accounts. The move is to curb money laundering, conflict of interest and insider trading, but it will touch on Kenya’s richest including former First Lady Mama Ngina Kenyatta who under Ropat Nominees owned over 22 percent of Commercial Bank of Africa now NCBA after its merger with NIC bank.

Anyway, let us cusp down the billionaires who have had interests in Kenya, shall we?

The richest person in the continent, according to Forbes Africa, is Nigeria’s Aliko Dangote at $10 billion (Sh1 trillion) meaning he can finance almost the entire budget of President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee government.

The bulk of his wealth is held under Dangote Group whose hydra of business interests sweep across cement manufacturing, sugar refineries, IT, logistics, agriculture, energy, food and beverages.

If you buy Adidas products you feather the nest of the 58 year old Sawiris

Dangote, 62, had registered two companies and planned to enter the Kenyan cement market in 2018 but nabobs in government demanded such heft kickbacks he relocated his dream to Ethiopia.

The second richest African is Egypt’s Naseef Sawiris at $6 billion (Sh600 billion) who inherited the construction and chemical divisions of the family’s Orascom conglomerate. But three-quarters of his fortune is now tied to his Sh400 billion stake in Adidas, the German sports apparel firm.

If you buy Adidas products you feather the nest of the 58 year old Sawiris-whose family are the largest shareholders of Lafarge, the majority shareholders in Kenya’s Bamburi Cement which is listed at the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE).

Other shareholders being seasoned stockbroker Jos Konzolo and former media man Peter Kibiriti

South Africa’s Koos Bekker is number 11 through his $2.5 billion (Sh250 billion) bonanza made through Africa media giant, Naspers. Bekker chairs Naspers which owns Multichoice and Dstv with operations in Kenya where OLX, now Jiji, was a household name until Naspers sold it to Genesis of Nigeria.

Bekker, 67, became the tale of investment fables when coined one of the world’s largest fortunes with a single bet. He pumped $32 million (Sh320 million) of Naspers money for a 50 percent stake in Chinese technology startup Tencent in 2001.

Tencent runs WeChat, both the MPesa and WhatsApp of China. Tencent gradually became the world’s largest gaming, venture capital and social media companies with Bekker’s single investment shot multiplying 500 times over to $133 billion (Sh1.3 trillion) of which he has diluted over 70 percent in 15 years.

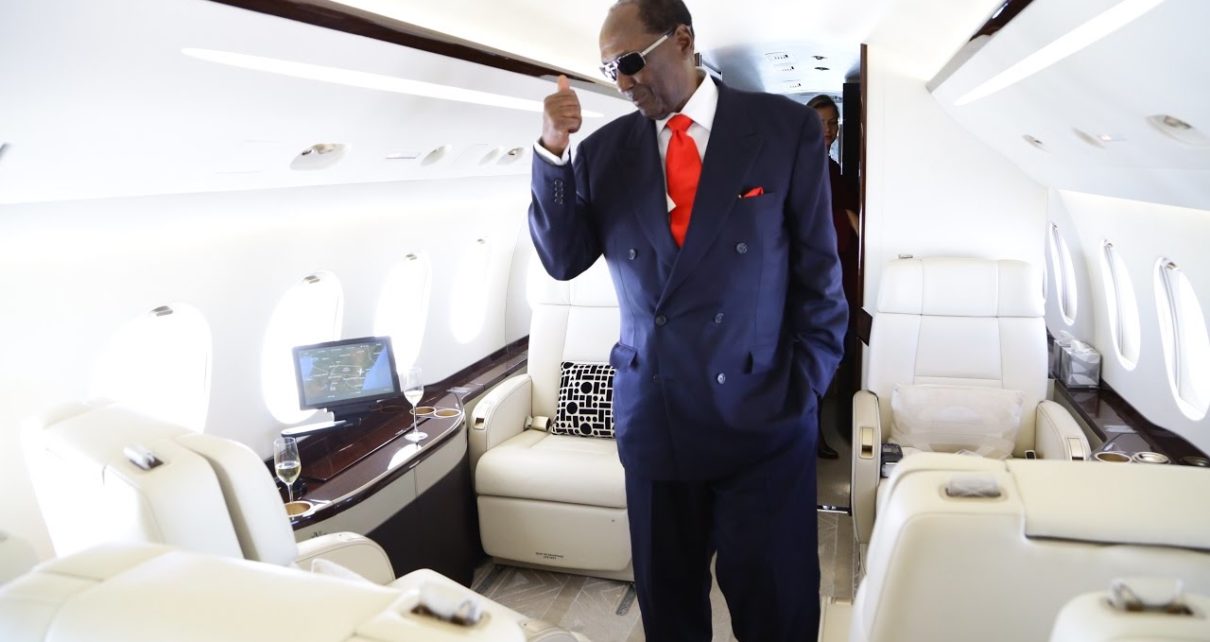

Then there is Strive Masiyiwa of Zimbabwe, 19th on the Forbes list with $1 billion (Sh100 billion) through 50 percent shares in Econet Group. His Econet Wireless was Kenya’s third telco by 2008-the other shareholders being seasoned stockbroker Jos Konzolo and former media man Peter Kibiriti.

Econet was later sold to India’s Essar Group and became Essar Telcom in 2009 under Yu Mobile. It was later sold in a mixed deal in 2015 when Yu Mobile became Telecom Kenya-with Safaricom acquiring its network and other IT assets while Airtel bought its over 2.5 million subscribers.

Looking at the Forbes Africa rich list, you will realize that the ploys, tricks, and traps in which money has been made has never changed

The 58 year old Masiyiwa, who has other interests in hospitality, financial services, media and renewable energy, is still active in Kenya. He chairs Liquid Telecom, a subsidiary of Econet Global, based along Mombasa Road. If you were active in sports betting then know that Liquid ensured your wins went through via having betting companies as clients.

Looking at the Forbes Africa rich list, you will shortly realize that the ploys, tricks, traps, gambits, variations and stratagems in which money has been made in truck loads, has never changed down all geological ages.

The late British management guru Robert Heller in his 1986 effort, The Age of the Common Millionaire, notes that “the millionaire earns his title by selling, or being able to sell, some property some product, some service or idea for more than cost. The wider the gulf between cost and realized value, the more rapidly the players gets his ultimate reward.”

Heller informs us on good authority that the “breakthrough, the searing stroke of genius, lies in spotting a demand, latent and blatant and simultaneously noting how that demand can be satisfied at the necessary premium over the cost of supply.”

And fewer have been lucky in Kenya than the Kenyattas, inheritance speaking

The knack for making money though manifests itself in various guises disguised as luck, timing, genius, ruthlessness, insight, as opportunism or stubbornness, but at the end of the day, the First Law of Millions states that “every millionaire creates wealth at somebody else’s expense.”

Majority of those who scale the financial uplands do it in the easiest ways known: Solving human problems and charging for it. And it is easier to make a million now than when your father was the height of his mother’s petticoat through technology as the fourth Industrial Revolution and attendant globalization.

But that half of Africa’s dollar billionaires inherited their fortunes and growing means we should spare some time on it: How come some families grow inherited wealth and others take it to the sands like the Karume family?

Well, surveyed closely, inheritance has the disadvantage of ‘remittance addiction’ or dependency which is worsened by ingratitude, entitlement, laziness and succeeding heirs having thinning drive and genius of the parent who produced it.

And fewer have been lucky in Kenya than the Kenyattas, inheritance speaking. Since the patriarch, founding President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta died in August 1978; the family wealth has stupendously nosed north.

When Jomo died, Brookside Dairies, the country’s largest milk processor was not on the cards

Kenyatta Inc. is now one of the biggest business dynasties with interests in real estate, property, ranching, healthcare, large scale agriculture, education, hospitality, dairy farming, equities, timber, aviation, media and banking.

When Jomo died, Brookside Dairies, the country’s largest milk processor was not on the cards. Or Mediamax Network Ltd which owns K24, People Daily and Kameme FM. Their Heritage Hotel chain was mostly at the coast and the tented camps in the Maasai Mara only came later.

The recent merger of NIC bank and Commercial Bank of Africa (to create NCBA) in which former First Lady Mama Ngina Kenyatta, Uhuru and Muhoho Kenyatta, hold a combined controlling stake, was not in the works. The merger will create Kenya’s third largest bank by assets after KCB and Equity. Also the Kenyatta stable controls the M-shwari end of the mobile money market under NCBA.

While the wealth of the Kenyattas has roots in state patronage, one can credit their prudent use of professional managers and advisors in its continued multiplication.

Only the business savvy in the family, in their case, Muhoho Kenyatta, are allowed to manage inherited fortune considering that incompetent heirs multiply geometrically in the second generation meaning “genetics is a poor management selection system” despite ready access domain knowledge and business loyalty.

The same cannot be said of the Karumes.

The old boy, politician and businessman Njenga Karume, could be nursing a cracked frown on the skull in his grave at how the billions he left, especially in real estate and hospitality, are dissipating fast.

The Kenyattas appear to have borrowed from Japan where inheritance grows under grandma’s eagle eye away from blundering male bloodlines

Besides professional managers and advisors, inherited wealth also grows through the secret of time and magic of compound interest even when lying idle in government securities at 10 percent per annually, give or take the vagaries of inflation.

Women are known to have better financial heads and the role of former First Lady Mama Ngina, the family matriarch in overseeing the expansion of Kenyatta Inc., cannot be gainsaid. The Kenyattas appear to have borrowed from Japan where inheritance grows under grandma’s eagle eye away from blundering male bloodlines.

The ventures of Kenyatta Inc., have spread their tentacles not just on the domestic front, but also exploring and exploiting markets beyond Kenya’s borders and Nigeria-based financial magazine, Ventures, has recently estimated the Kenyatta family fortune at a conservative $1 billion (Sh100 billion)-which knocks them off the list of Africa’s richest-as the wealth is family, not individually owned.

The richest in Africa are also in manufacturing, an area not many indigenous Kenyans get into

The other family in this league of inherited wealth and growing, are the Ndegwas, scions of former Central Bank Governor the late Philip Ndegwa-said to be the first Kenyan to bank a billion.

Ndegwa minted one of Kenya’s most

secured fortunes via First Chartered Securities, an indigenous investment

outfit founded in 1974 with some 20 civil servants and business moguls as

shareholders.

Ndegwa’s acquisition vehicle bagged the Insurance Company of East Africa (now

ICEA Lion with a 100 percent shareholding), before forays in re-insurance,

banking, agriculture, logistics, and real estate-where the property portfolio

was worth $100 million (Sh10 billion by 1999)- through its insurance arm alone!

The Ndegwa sons, James and Andrew split half of their family’s 25 percent stake

in NIC Bank-where they’re directors-worth Sh5 billion.

The Ndegwas have lately been divesting and in 2015 they offloaded agriculture and hospitality equipment company G-North & Son to businessman Paul Ndung’u Wanderi for an undisclosed sum. They also sold the ICEA building along Nairobi’s Kenyatta Avenue to JKUAT for Sh1.8 billion in 2017. While James and Andrew sit on boards in which they have stakes, First Chartered Securities is run by professional managers.

The aforementioned Karumes, on the other hand, are battling auctioneers.

The richest in Africa are also in manufacturing, an area not many indigenous Kenyans get into besides Chris Kirubi with Haco Industries and Kimani Rugendo with Kevian Kenya, makers of Afia juice.

There are three reasons Kenyan Africans hardly venture into manufacturing: Capital, culture and colonialism

Manufacturing in Kenya is dominated by muhindis, mzungus and foreign investors. How come Kenyans are hardly in manufacturing yet they are good copycats in areas with money to be made? Remember the- quail and simu ya jamii craze?

Manufacturing is also part of President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Big Four Agenda. The government has money to burn here.

The sector has been left to the Manu Chandarias (Mabati Rolling Mills), the Ravals (Devki Steel, Maisha Mabati, National Cement) and the Bhemji Shahs (Bidco Oil Refineries).

Indians, on the other hand, have a culture of communal saving for the capital, a culture of homespun industriousness

Take Bidco, the largest manufacturer of edible oils in East and Central Africa, and manufactures detergents, soaps, baking powder and canola enjoys a 49 percent share of the edible oils market in Kenya, and annual revenues of more than $500 million (Sh50 billion), according to Forbes Africa.

Bidco is owned by Bhimji Shah and his sons Vimal Shah and Tarun Shah who each control a third of the behemoth which distributes its products to 14 African countries.

The Shahs recently opened the $200 million (Sh20 billion) Bidco Industrial Park in Kiambu County.

There are three reasons Kenyan Africans hardly venture into manufacturing: Capital, culture and colonialism.

Most hardly have the cash outlay required. Attention to detail crucial in manufacturing is not part culture of most us while colonialism did not expose Kenyans to the rigour of production on industrial scales.

Indians, on the other hand, have a culture of communal saving for the capital, a culture of homespun industriousness and 300 years of British rule that inculcated the rigour of dealing with machines. Then there is history. Kenyans never went through Industrial Revolution, like mzungus.

Most muhindis are fourth generation Kenyans whose forefathers came here with nothing but a suitcase and manual skills to build the Uganda Railway which was completed in 1901.

With the end of the railway project these muhindis (Indian Coolies) stayed, started shops and controlled the retail trade in Kenya.

These muhindis also had the benefit of the outsider who has no hang ups doing anything to succeed in a foreign environment

In her 1989 book, Through Open Doors: A View of Asian Cultures, Cynthia Salvadori informs that among Indians who remained were skilled artisans – “carpenters, masons and blacksmiths” and that the blacksmiths “turned to motor mechanics”, carpenters became “timber merchants and started furniture factories” while the masons “built up construction companies.”

These muhindis also had the benefit of the outsider who has no hang ups doing anything to succeed in a foreign environment.

That the colonial government banned them

from owning farms and farm activities also pushed them to wholesale, retail and

manufacturing businesses.

Indeed, it’s here where the Indian work ethic spawned magic in lasting family

ventures; like Essajee Amijee&Sons, still dealing in glass for over 100

years, Broadways Bakers in Thika since 1950, Nairobi Rubber Stamp Makers since

1957 the year Turkoman Carpet Emporium was also founded.

A study carried out by Rwandese economist David Himbara found that 75 percent

of Kenya’s manufacturing sector is controlled by Asians with Kenyan Africans

clutching at a measly five percent. The study was done in 1995. Over 20 years

later, little has changed.